NASA/ISS

NASA/ISS

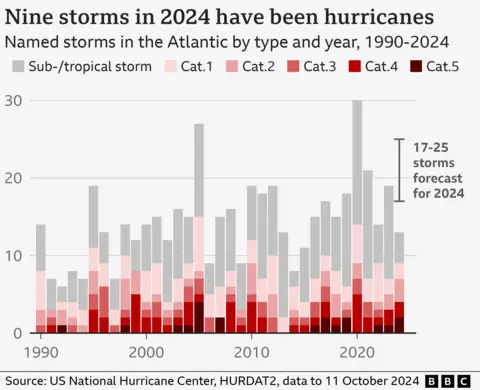

Hurricanes Helene and Milton – which have devastated parts of the south-east United States – have bookended an exceptionally busy period of tropical storms.

In less than two weeks, five hurricanes formed, which is not far off what the Atlantic would typically get in an entire year.

The storms were powerful, gaining strength with rapid speed.

Yet in early September, when hurricane activity is normally at its peak, there were peculiarly few storms.

So, how unusual has this hurricane season been – and what is behind it?

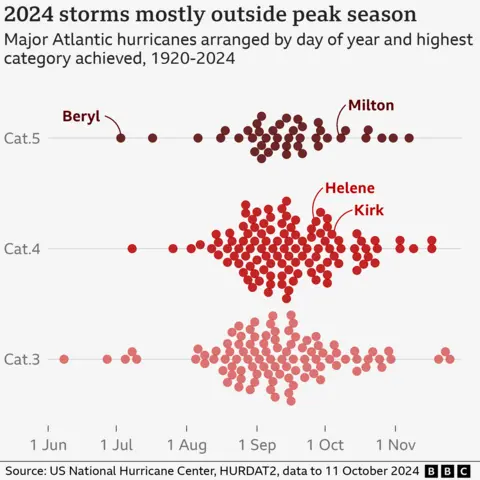

The season started ominously. On 2 July, Hurricane Beryl became the earliest category five hurricane to form in the Atlantic on records going back to 1920.

Just a few weeks earlier in May, US scientists had warned the 2024 season from June to November could be “extraordinary”.

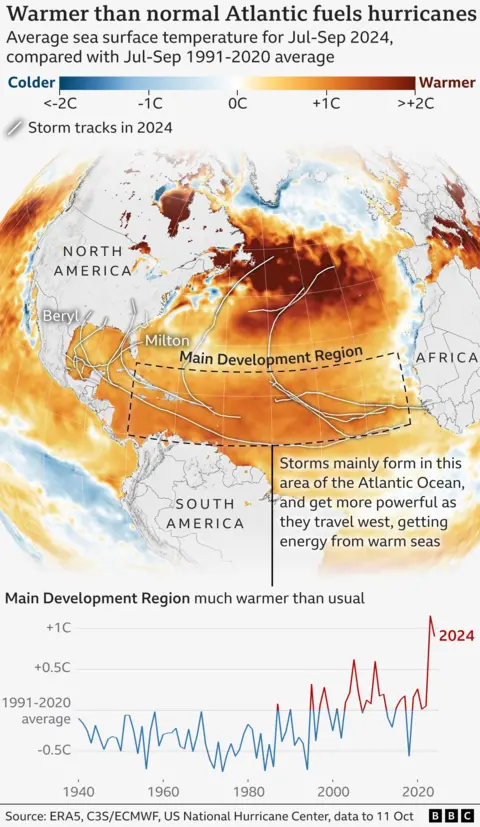

It was thought that exceptionally warm Atlantic temperatures – combined with a shift in regional weather patterns – would make conditions ripe for hurricane formation.

So far, with seven weeks of the official season still to go, there have been nine hurricanes – two more than the Atlantic would typically get.

However, the total number of tropical storms – which includes hurricanes but also weaker storms – has been around average, and less than was expected at the start of the year.

After Beryl weakened, there were only four named storms, and no major hurricanes, until Helene became a tropical storm on 24 September.

That is despite warm waters in the tropical Atlantic, which should favour the growth of these storms.

Across the Main Development Region for hurricanes - an area stretching from the west coast of Africa to the Caribbean - sea surface temperatures have been around 1C above the 1991-2020 average, according to BBC analysis of data from the European climate service.

Atlantic temperatures have been higher over the last decade, mainly because of climate change and a natural weather pattern known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.

The recipe for hurricane formation involves a complex mix of ingredients beyond sea temperatures, and these other conditions were not right.

“The challenge [for forecasting] is that other factors can change quickly, on the timescale of days to weeks, and can work with or against the influence of sea surface temperatures,” explains Christina Patricola, associate professor at Iowa State University.

Researchers are still working to understand why this was the case, but likely reasons include a shift to the West African monsoon and an abundance of Saharan dust.

These both hampered storm development by creating unfavourable conditions in the atmosphere.

But even during this period, scientists were warning that the oceans remained exceptionally warm and that intense hurricanes were still possible through the rest of the season.

And in late September, they came.

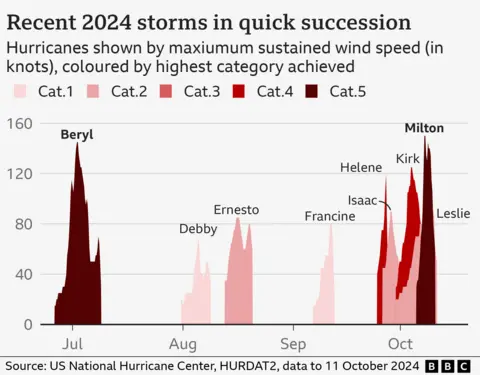

Starting with Helene, six tropical Atlantic storms were born in quick succession.

Fuelled by very warm waters – and now more favourable atmospheric conditions – these storms strengthened, with five becoming hurricanes.

Four of these five underwent what is known as “rapid intensification”, where maximum sustained wind speeds increase by at least 30 knots (35mph; 56km/h) in 24 hours.

Historical data suggests that only around one in four hurricanes rapidly intensify on average.

Rapid intensification can be particularly dangerous, because these quickly increasing wind speeds can give communities less time to prepare for a stronger storm.

Hurricane Milton strengthened by more than 90mph in 24 hours – one of the fastest such cases of intensification ever recorded, according to BBC analysis of data from the National Hurricane Center.

Scientists at the World Weather Attribution group have found that the winds and rain from both Helene and Milton were worsened by climate change.

“One thing this hurricane season is illustrating clearly is that the impacts of climate change are here now,” explains Andra Garner from Rowan University in the US.

“Storms like Beryl, Helene, and Milton all strengthened from fairly weak hurricanes into major hurricanes within 12 hours or less, as they travelled over unnaturally warm ocean waters.”

Milton also took an unusual, although not unprecedented, storm path, tracking eastward through the Gulf of Mexico, where waters have been exceptionally warm.

“It is very rare to see a [category] five hurricane appearing in Gulf of Mexico,” says Xiangbo Feng, research scientist in tropical cyclones at the University of Reading.

Warmer oceans make stronger hurricanes - and rapid intensification - more likely, because it means storms can pick up more energy, potentially leading to higher wind speeds.

What about the rest of the season?

US forecasters are currently watching an area of thunderstorms located over the Cabo Verde Islands off the west coast of Africa.

This could develop into another tropical storm over the next couple of days, but that remains uncertain.

As for the rest of the season, high sea surface temperatures remain conducive for further storms.

There is also the likely development of the natural La Niña weather phenomenon in the Pacific, which often favours Atlantic hurricane formation as it affects wind patterns.

But further activity will rely on other atmospheric conditions remaining favourable, which are not easy to predict.

Either way, this season has already highlighted how warm seas fuelled by climate change are already increasing the chances of the strongest hurricanes – something that is expected to continue as the world warms further.

“Hurricanes occur naturally, and in some parts of the world they are regarded as part of life,” explains Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, USA.

“But human-caused climate change is supercharging them and exacerbating the risk of major damage.”

.png)

3 weeks ago

3

3 weeks ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·