CNN —

Few scholars have experienced the fickle nature of fame as dramatically as Ibram X. Kendi in the past three years.

Kendi, author of the New York Times #1 bestseller, “How to Be an Antiracist,” became an intellectual celebrity in the summer of 2020 after his books became a go-to source for millions of Americans trying to make sense of the murder of George Floyd. He was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” became a sought-after commentator on race and helped add a new word to the way we talk about it: antiracist. The term means to actively fight against racism rather than passively claim to be non-racist.

Then came a backlash. Kendi’s books were banned by some school libraries and he was accused by conservatives of corrupting children and offering a grim view of America that casts everyone as a racist. He also became the central villain in a GOP-led campaign to purge the teaching of systemic racism in American public schools. The campaign took off following the massive wave of racial protests that swept across the country in the wake of Floyd’s death, which drew the support of many White people, including students.

Kendi says the current campaign against what one conservative commentator calls “systemic wokeness” is an effort to halt the antiracist momentum generated by the Floyd protests. When asked what happened to that momentum, Kendi gives a wry chuckle.

“The momentum was just crushed by a pretty well-organized force and movement of people who are seeking to conserve racism,” he says. “Who’ve tried to change the problem from racism to antiracism. And who’ve tried to change the problem from police violence to the people speaking out against police violence.”

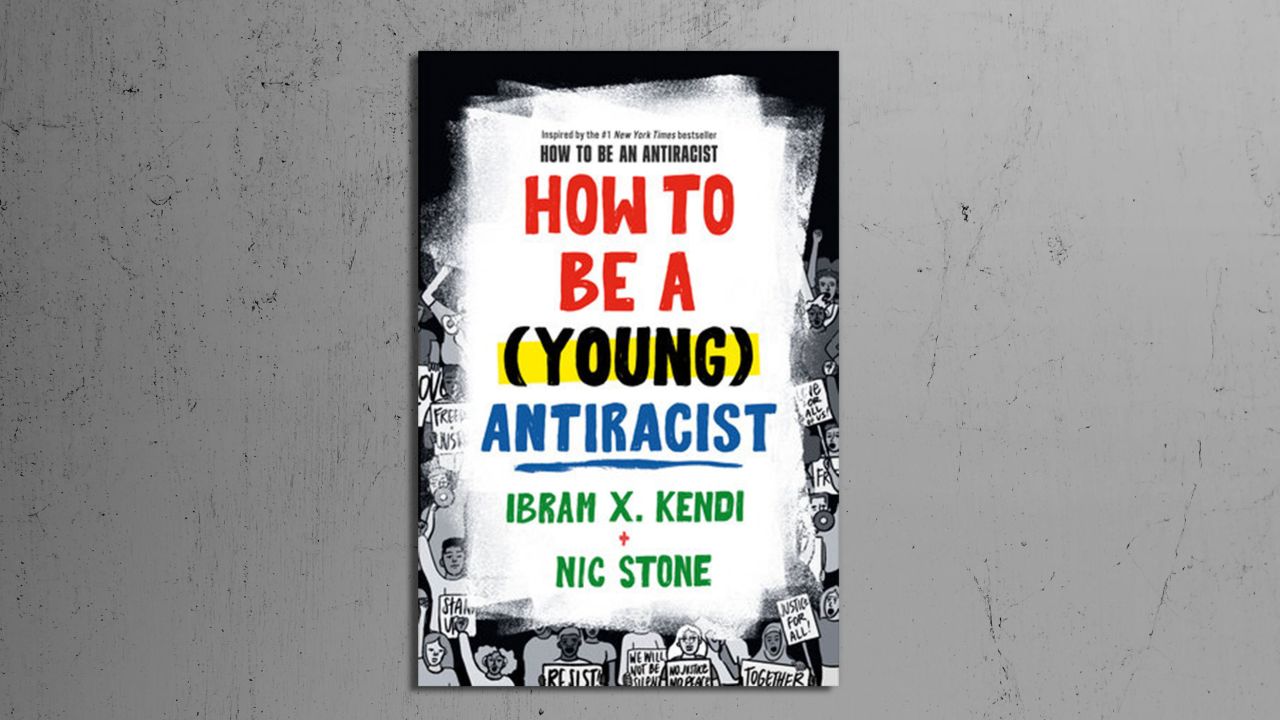

Kendi has written a new book, “How to Be a (Young) Antiracist,” that could help recapture some of that momentum. He and co-author Nic Stone have reframed his aforementioned 2019 bestseller, this time for young adults. This version, according to the book’s publisher, serves as an instruction manual for youth “seeking a way forward in acknowledging, identifying and dismantling racism and injustice.”

The book offers those lessons by recounting how Kendi, as a young person, absorbed some of the same racist beliefs he now argues against. The confident, professorial Kendi that most see in public is replaced in the book by a younger version who struggled with doubts over his intelligence. The book features some of the most personal disclosures of Kendi’s public career.

What may be most surprising, though, is the book’s tone of optimism. Despite the change in the political climate since Floyd was murdered nearly three years ago, Kendi still believes racism can be vanquished. He says it’s It’s not an all-powerful “deity” that can never be defeated. That’s one reason he remains hopeful about antiracist activism.

“Racist ideas are not natural to the human mind,” he wrote. “In the grand scope of human existence, race and racism are relatively young. Prior to the construction of race and racism in the 1400s, human beings saw colors but didn’t group them into continental ‘races’ and attack wholly made-up positive and negative characteristics to said races. That’s something we learned to do.”

Kendi, is currently a professor at Boston University and founding director of its Center for Antiracist Research. He recently talked to CNN following the release of his book. His comments have been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

You said near the end of your book that this book stretched you in a way that no other had before. How so?

I think because of the depths of vulnerability that I had to reach, and what I had to express publicly. It’s very difficult to be vulnerable with ourselves and to be honest about those hurtful and harmful things we’ve said and done. It’s yet another thing to be willing to share that with the public. And to deal with the shame that other people would know. That’s why it was so difficult.

You talk in the book about having doubts about your own intellect because of standardized testing. How did you overcome those doubts?

I didn’t fully overcome those doubts until I started rethinking what it means to be intelligent. We have been taught that the more intelligent you are, the better test scores you’ll get. But the more I understood intelligence, the more I realized that intelligence should be defined as a great capacity to know. And so I knew that I did have a desire to know, particularly as a researcher. For me it allowed me to better understand my own intelligence.

Are people taught racism, or are human beings born with this instinct to assign value to skin color? Some people think racism is just part of being human.

This is hotly debated among scientists and scholars, particularly the instinct part. Based on my research, I don’t think that people are born racist or antiracist. But I think depending on the environment that they are raised in, they go in one or the other direction.

I think human beings are taught instinctually to protect ourselves. When you grow up in a racist society where you’re taught that those “other people” are the source of your pain, those “other people” are not like you because they look differently or because they have different hair texture, it can then lead to people instinctually wanting to protect themselves from those “other people.”

But what if we taught that skin color is as irrelevant as the color of one’s shirt? What if we taught that hair texture is as irrelevant to the underlying person’s humanity as the glasses that they are wearing? We can teach people to think differently about people who look different to the point where they’ll see the humanity in that person, despite different skin color and hair texture.

That’s very optimistic. It reminds of something else I read in your book. You said racism isn’t this all-powerful deity that can’t be defeated. What do you mean by that?

Researching the history of racism — who created it, for what purpose, how its evolved over the last nearly 600 years, how it’s spread around the world, how it’s impacted people — it’s allowed me to really take a step back and see the structure, which then allows me to believe that it can all be deconstructed. Somebody built this (racism). And they’re rebuilding it. But you can actually deconstruct it. Anything that can be constructed, like racism, can be deconstructed.

In the meantime, what kind of practical advice would you give parents about how they can talk to their kids about incidents like in Memphis, where a young Black man (Tyre Nichols) was beaten to death by police officers?

First, it’s important for parents to talk to their children about what happened in Memphis. It’s important because the child is going to ask why: “Why did this happen to him? He wasn’t doing anything wrong. He kept doing what the officers asked him to do, but they kept beating him?” In answering those questions, you have to talk about the pervasive violence in American policing, particularly toward Black and brown people. You have to talk about the pervasiveness of racist ideas that imagine that Black people are dangerous.

At one point at your book, you’ve said that there is no neutrality in the struggle against racism. What does that mean?

Currently there are deep racial inequities in our society. Black people are more likely to die of police violence, of heart disease, of cancer. They’re more likely to be impoverished. They’re less likely to have wealth. They’re more likely to be incarcerated, and on and on. That’s the status quo. If you “do nothing,” what happens to that status quo? You’re part of this society. It’s not like this is a war happening across the world, and you’re deciding to be neutral. No, this war is happening in your own community, in your own society.

And those inequities are the outgrowth of that war. If you do nothing, what happens? It persists. Which is to say, you contributed to its persistence because you’ve chosen to not challenge it. So one’s feigned neutrality is actually being complicit with racism. That’s why it’s important for us to know that we’re either being racist through our actions or inaction, or being antiracist through our actions.

Parents and education officials have banned or tried to ban your books across the country. GOP politicians in Florida have passed laws that say certain aspects of African American history can’t be taught if they make White people feel guilt or anguish. What’s your reaction to this?

It doesn’t surprise me because as a student of history, abolitionist literature was almost totally banned in the South, especially after the 1830s. During the civil rights movement, particularly throughout the Jim Crow era, you had all sorts of books that told the truth about slavery, about Reconstruction, about American racism, that were banned in many schools.

For the better part of American history, books about people of color or racism have largely been challenged or banned. What’s happened (lately) is more consistent with American history. But just as we fought those book bans in the past or just as my enslaved ancestors found ways to read abolitionist literature, so too can we fight and still read today.

How challenging has it been for you – physically, emotionally, and spiritually – to constantly talk about this complex issue of racism and to be the object of hate from people who don’t know you?

In many ways it has certainly been difficult, just as it as for a physician who routinely treats people who are sick, to have to continuously diagnose, identify and describe the sickness of racism in our society. But at the same time, like physicians who do this every day, it’s so necessary. And we’re so committed to this work and to healing people and society.

The greatest difficulties are when people try to delegitimize me and my work because they disagree with the evidence. They don’t want to make assessments based on research. They want to make assessments based on their own ideology, or what’s best for their own political faction. Clearly that’s difficult. When people threaten me in all types of ways, of course that’s difficult. But at the same time, I knew what I was getting into. And I’m figuring out ways to get through every day.

So how do you get through the days?

I’ve learned what can be too much. You spend a lot of time trying to care for humanity. It’s important to recognize that you’re part of that humanity. It’s important to care for yourself as well. I’ve been figuring out ways to do that, particularly around my physical and emotional health.

John Blake is a Senior Writer at CNN and the author of “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”

.png)

1 year ago

5

1 year ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·