Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

In 2020, about six million Latinos identified themselves as racially Black in addition to ethnically Latino, and for decades, millions have done so on the census. Now the federal government is considering a proposal that threatens to erase these numbers and further aggravate the longstanding problem of undercounting our nation’s citizens with Black ancestry. But we have until April 12 to share our concerns with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the federal agency in charge of designing how race and ethnicity questions are presented on the census and other government data forms.

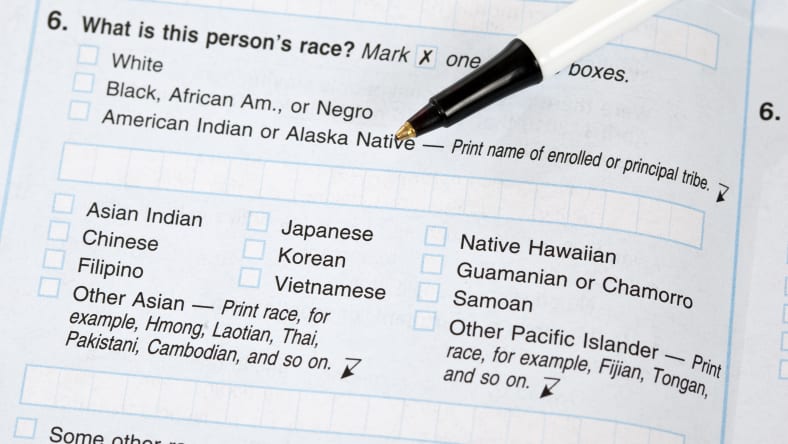

The racial and ethnic classifications that the government devised in 1977 (and revised in 1997) were for the specific purpose of facilitating the application of civil rights laws. By comparing the demographic count of individuals by race to the statistical presence of each racial group in workplaces, housing purchases and rentals, and access to mortgages, racial disparities can be uncovered and then investigated for discriminatory practices. The current format first asks whether someone’s ethnicity is Hispanic-Origin, followed by a second question of what is their race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Other). This two-question format recognizes that within Latino ethnicity there are racial differences.

The OMB proposal now being considered will combine both inquiries into a single question of “What is your race or ethnicity?” and collapse Latino/Hispanic ethnic identity into the list of racial categories with Black. This proposed conflation of ethnicity with race risks obscuring the number of Afro-Latinos and the monitoring of socio-economic status differences of Latinos across races that exist.

For Afro-Latinos and others with dark skin, the race and ethnicity OMB proposal erases how they experience racism compounded by their Blackness. We need data that can measure the existence of racial disparities amongst Latinos. As the Pew Research Center and other researchers have long noted, there are distinct social outcomes based on labor market access, housing segregation, educational attainment and prison sentencing that vary for Latinos if they are dark-skinned and especially if they are visibly Afro-Latino. This is not an insignificant population, given the fact that approximately 90 percent of the enslaved Africans who survived the Middle Passage voyage were taken to Latin America and the Caribbean.

Yet the OMB is poised to sacrifice the accurate count of Afro-Latinos ostensibly to solve a problem that is largely a statistical coding invention of the U.S. Census Bureau. Latinos who do select a race and then add a country of origin have been repeatedly and wrongly coded as “Some other race” and thus systematically mischaracterized as racially confused. Specifically, when Latinos have checked a racial category on the census such as “white” and then inserted additional information about their country of origin such as Argentinean, the census has coded and counted such Latinos as a non-responsive some-other-race-category person to be folded into “two or more races.” To be clear, that racially white Latino person of Argentinean ethnic origin is counted by the census as multiracial and not white.

In turn, the Census Bureau portrays the approximately 40% of Latinos who include a country of origin in their racial responses like a white Latino Argentinean as being racially confused and in need of a new way to respond to the government inquiry into race and ethnicity. Perhaps it is more accurate to conclude that U.S. government officials are the ones confused about the existence of racial difference within the pan-ethnic population of Latinos, rather than pathologizing how Latinos attempt to reflect that intersectional reality. Afro-Latino scholars have much expertise to offer regarding improved methods for enhancing Latino responses to race questions that don’t sacrifice the count of Afro-Latinos, but they have not been allowed a seat at the table.

Moreover, the government testing of the proposed combined question recorded a race for significantly fewer Latinos both statistically and substantively, in addition to failing to test in regions where Afro-Latinos are densely populated. It is thus highly problematic to draw conclusions from this inadequate testing about how the proposal may affect the count of Afro-Latinos. The national racial reckoning following the 2020 murder of George Floyd has only increased the Black race consciousness of Latinos, which could not possibly be captured by the now-dated 2010 and 2015 testing. Within the narrow confines that the government tested, the number of Latino respondents checking “Some other race” declined. But at what cost to fully counting those Latinos who also identify as Black across the country?

Proposing to insert “Latino” as a category commensurate with “Black” not only situates Blackness as foreign to Latino identity it also encourages a view of the Black category as only pertaining to non-Latinos. This would impede the legal system’s ability to statistically detect and sanction an employer who systematically rejects qualified Afro-Latino applicants while simultaneously hiring white Latinos. Without racially specific Latino census data to compare to the business’s hiring pattern, an employer’s racism would be swept away with the defense “I do hire Latinos.”

As I methodically document in the book “Racial Innocence: Unmasking Latino Anti-Black Bias and the Struggle for Equality,” too often, Latino decision-makers deny Afro-Latinos access to jobs, homes, public accommodations and fair treatment in schools and the criminal justice system. In other words, the anti-Black bias that imploded the Los Angeles City Council in October 2022, is not a one-off dynamic amongst Latinos. Former City Council President Nury Martinez, who was caught on a leaked audio recording making racially insensitive remarks, has lots of company.

Whiteness and Blackness make a real difference in the lives of Latinos, and we need statistical data that helps to measure that for social justice intervention. The present government proposal will likely impede the pursuit of racial equality and should be rejected.

Tanya Katerí Hernández is a professor of law at Fordham Law School and a member of the Latino Is Not a Race Collective.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·