Activists swiftly condemned the Uganda Parliament, which on Tuesday passed a second version of the Anti-Homosexuality Act after the country’s president returned the controversial legislation for revisions.

The latest movement on the anti-LGBTQ bill in Kampala signals that it will likely be signed into law despite stern warnings from the international community and global businesses.

Activists and U.S. officials believe the Anti-Homosexuality Act — which would criminalize LGBTQ+ identity — would be a major human rights setback in Uganda, on the African continent and around the world.

Kenyan gays and lesbians and others supporting their cause wear masks to preserve their anonymity as they stage a rare protest against Uganda’s tough stance against homosexuality and in solidarity with their counterparts there on Feb. 10, 2014 outside of the Uganda High Commission in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo by AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

Kenyan gays and lesbians and others supporting their cause wear masks to preserve their anonymity as they stage a rare protest against Uganda’s tough stance against homosexuality and in solidarity with their counterparts there on Feb. 10, 2014 outside of the Uganda High Commission in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo by AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)“We have grave concerns,” White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told theGrio last week when asked about the latest actions related to the bill.

“This bill is one of the most extreme anti-LGBTQ+ laws in the world,” added Jean-Pierre, who said the U.S. is engaged with Uganda’s government “at the highest level on this issue.”

Supporters of the Anti-Homosexuality Act say a new law is necessary to counter what they believe to be efforts by LGBTQ Ugandans to groom children into homosexuality, Reuters reported. Before Tuesday’s vote, speaker Anita Among called on her colleagues to support the bill despite international criticism, to “protect” Ugandans. “Let’s protect our values [and] our virtues,” Among said. “The Western world will not come and rule Uganda.”

The Uganda Parliament reconsidered the bill at the request of President Yoweri Museveni, who sought to add provisions.

Frank Mugisha, a human rights advocate in Uganda, told theGrio that the bill that passed Tuesday afternoon local time is essentially the same bill that was passed in late March with minor revisions.

The new bill contains amendments related to compelling one to report “aggravated homosexuality” when it involves a minor or if someone is abused. It also retained a provision that would allow a landlord to deny someone the ability to rent a home or apartment if someone is known to be homosexual.

Museveni now has 30 days to sign the bill into law.

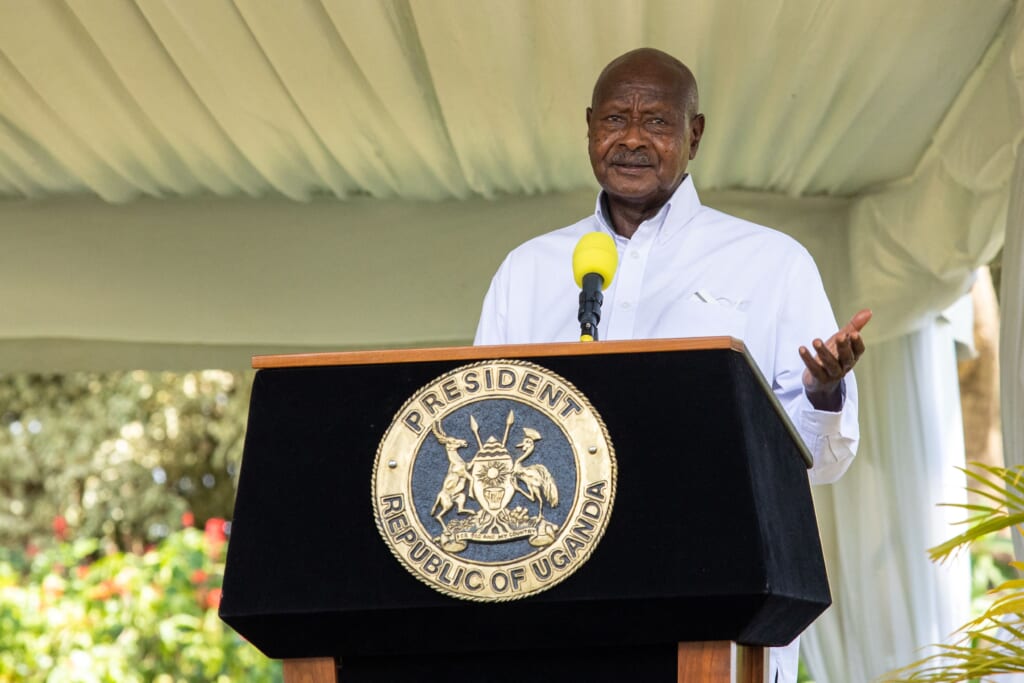

Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni speaks during a joint press conference with Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on July 26, 2022 at the State House in Entebbe, Uganda. (Photo by BADRU KATUMBA/AFP via Getty Images)

Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni speaks during a joint press conference with Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on July 26, 2022 at the State House in Entebbe, Uganda. (Photo by BADRU KATUMBA/AFP via Getty Images)Mugisha, who is risking his life and freedom as a vocal LGBTQ+ advocate in Uganda, said his organization, Sexual Minorities Uganda, and others would challenge the Anti-Homosexuality Act in court once it becomes law.

“There are so many irregularities around this legislation,” Mugisha said. “It contradicts our own constitution and international treaties.”

He said he is “very confident” about their chances in the court system. The bill, Mugisha argued, is filled with “propaganda and conspiracy theories.”

On a personal level, Mugisha admits that he is scared for his life and freedom, as well as the lives of his staff and other LGBTQ+ Ugandans, who would become subject to the penalties in the Anti-Homosexuality Act.

“We are going to see an increase in violence even before the president signs the bill and we are also going to see blackmail and extortion,” he predicted. “Many people will be arrested.”

Bishop Joseph Tolton, an activist and religious leader who has done missionary work in Uganda, slammed the passage of the latest version of the bill, which he said “masquerades as a specific assault on the humanity of queer Ugandans,” adding “underneath that thin veneer is a country making a decision that it will bow to the throne of autocracy, embrace nationalism and participate in the reign of white supremacy globally.”

Tolton, the executive director of the Pan-African advocacy group Interconnected Justice, called out the “unholy alliance” between far-right white Christian nationalists in America and their African counterparts at the center of Uganda’s anti-LGBTQ movement.

A Ugandan man is seen during the third Annual Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Pride celebrations on Aug. 9, 2014 in Entebbe, Uganda. (Photo by AP Photo/Rebecca Vassie, File)

A Ugandan man is seen during the third Annual Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Pride celebrations on Aug. 9, 2014 in Entebbe, Uganda. (Photo by AP Photo/Rebecca Vassie, File)Mugisha described the influence of white conservative Christians in Uganda as “serious,” telling theGrio, “they have access to the highest offices in the country and they have a lot of money.”

He explained, “They come here, they partner with politicians [and] they have a lot of power.”

Mugisha said it’s difficult to hold them accountable “because they raise this money from churches and they distribute to their partners as they want.”

However, there are U.S. government efforts to hold Uganda accountable for its anti-homosexuality bill as officials seem poised to withhold funding for Uganda’s PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) programs.

PEPFAR has provided needed aid for health care throughout Sub-Saharan Africa since President George W. Bush established it in 2003.

(L-R) Uganda President Yoweri Museveni shakes hands with U.S. President George W. Bush in the Oval Office at the White House on Oct. 30, 2007 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

(L-R) Uganda President Yoweri Museveni shakes hands with U.S. President George W. Bush in the Oval Office at the White House on Oct. 30, 2007 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)Last week, U.S. officials postponed a crucial meeting with PEPFAR Uganda over concerns about the impact of the anti-homosexuality legislation. A spokesperson for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) told theGrio that the postponement was necessary to give agency officials more time to assess the legal and programmatic implications of the potential new law.

The spokesperson, who commented on background in order to speak on diplomatic issues, said the agency advocates and supports programs to protect the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals around the world and has significant concerns about how the bill will “threaten the human rights of Ugandan citizens, jeopardize progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS, deter tourism and investment in Uganda and damage Uganda’s international reputation.”

Workers unload medical supplies to fight the Ebola epidemic from a USAID cargo flight on Aug. 24, 2014 in Harbel, Liberia. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Workers unload medical supplies to fight the Ebola epidemic from a USAID cargo flight on Aug. 24, 2014 in Harbel, Liberia. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)There is $500 million in annual health assistance and assistance in other sectors on the table, the USAID spokesperson noted.

“The impact of our PEPFAR funding, which is aiding Uganda to end HIV/AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, would be severely compromised if we were not able to provide services to Ugandan citizens,” said the spokesperson.

Mugisha compelled the U.S. government “not to support Uganda in any way,” reiterating USAID’s concerns that the anti-LGBTQ law would make it difficult for the agency to achieve its goals. As the National Institutes of Health points out in a study, homophobia continues to fuel the AIDS epidemic in Africa.

“The impact will be huge,” said Mugisha. “PEPFAR provides life-saving medication for many Ugandans who are on HIV/AIDS medication and also PEPFAR funds the technical work and the support for our Ministry of Health.”

The activist also called for more “progressive voices” to speak out against Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act. Not doing so, he said, will lead to ramifications across the continent.

Mugisha warned: “Once it is signed by the president in Uganda, it is definitely going to spread out in other countries.”

Gerren Keith Gaynor is a White House Correspondent and the Managing Editor of Politics at theGrio. He is based in Washington, D.C.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. TheGrio’s Black Podcast Network is free too. Download theGrio mobile apps today! Listen to ‘Writing Black‘ with Maiysha Kai.

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·